- Lloyd Alexander

- 1964

- Read: 03/28/25

- Grade: B-

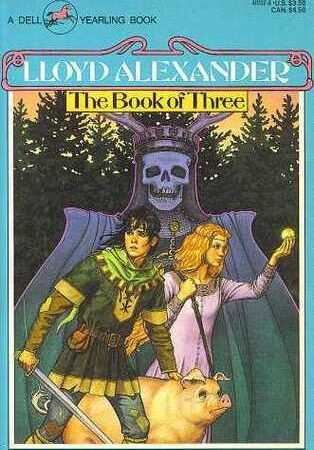

There are few books who can claim a more formative role in my life than this one. I couldn’t say for certain the year, but what can be sure is that in the earliest years of the 1990s, the edition pictured above was one of the precious purchases from the quite magical yearly book fair at Buckhorn Elementary School, and I’ve been reading it (not my original copy unfortunately) ever since. There was little about my time at that lovely little school that is more solidly fixed in my memory than that book fair, and some of my purchases have become fixtures of my emotional attachment to books. These items ranged from seemingly innocuous trifles (yet still impactful) such as the scholastic Sport Shots(which I still proudly own),

Classics such as Aliens Ate My Homework

Jeremy Thatcher the Dragon Hatcher

The Eyes of Kid Midas

Hook

And, awaited with baited breath and eager eyes, whatever the most recent edition was of that titan of tot-horror…Goosebumps.

The last of these deserves to have its own wing in the archive, but those are efforts for other eves. Suffice it to say, all of these texts, and others besides, have their own special place in my heart owing in no small part, I imagine, to the fact that I chose them for myself. Ultimately, even among these titans of my childhood, The Book of Three stands apart.

The evidences of the scope of this impact are legion. Many of my first written characters were named Taran (not to mention more than a few RPG characters to include a ranger in D&D, a Thunderbolt pilot in Battletech, and an Orlock gang leader in Necromunda), nearly every early online RPG character from Gemstone III, to Dragonrealms, to Everquest, was a bard named Turloyen in direct homage to the “Great Belin!” shouting Fflewddur Fflam, and if the language of the Evermore is a direct descendant of Neverland, something of its accent is that of Prydain.

Now it’s long past time I reverse the accidental pattern of putting the good news up front with these reviews. Upon further examination, it always seems as though my critiques are harsher than I intend, and I always have to sign off with some manner of apology to smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss. To remedy this deformity of organization, I’ll open here with the things that I generally view as overall weaknesses and close more jubilantly as is my wont in this instance.

The only major complaint I have is the abrupt and convenient nature of the climax, so it seems best to begin there. The whole novel might be accused of failing to drive to a point and being more than a little spontaneously episodic in nature. I find this rather believable in an adventuring party being led by a young man who’s never before been off the farm. Ostensibly, the culmination of the novel is Taran, Eilonwy, Fflewdur, Gurgi, Doli, and Melyngar’s race to beat the armies of the Horned King to Caer Dathyl to warn the Sons of Don of the approaching danger. Setting aside the fact it would be the height of incompetence for the Sons of Don to let a massive army sneak up on them in the bold light of day, the novel never gives a clear reasoning as to why Taran’s mission is in fact the difference between victory and defeat. Moreover, the novel doesn’t even give the heroes a chance to test the hypothesis. Instead, the culmination of events sees the deus ex machina go all the way to plaid and not only have the suspected dead Gwydion return suddenly but defeat the Horned King using the latter’s secret name.

On their own, neither of these events is very out of the way for a fantasy story. The sudden reemergence of a hero has a long history, and words of power are one of my personal favorite devices. However, in this instance the first of these steals the agency from the protagonists of the story, and the second has no groundwork laid anywhere in the narrative, so it feels completely arbitrary.

Owing to the manner of his exit from the stage during the events inside the Spiral Castle, it was not difficult to predict that the heroic Gwydion was not dead as Taran had supposed, and having him return at some pivotal moment would normally be quite fitting. However, here, the reader is awkwardly aware of the effect of his return before the fact of his return. The Horned King, strangely isolated and away from his army, is simply and suddenly consumed in an inexplicable fashion, and we are left to hear the explanation after.

The second, and perhaps more egregious, of these weaknesses is the use of the Horned King’s secret name as the method of his defeat. It is not only that this concept has no basis in the preceding narrative, but, like a time-turner, it creates difficulties for every story that comes after it, namely the question as to why the heroes don’t simply use Hen Wen’s oracular powers to divine the names of all of their enemies and thereby circumvent all the succeeding dangers. One good thing about this climax is that it prevents the plot from violating the precept of Chekhov’s Gun. After an entire narrative where all the major parties were bent solely on procuring the powers of this oracular pig, it would be an insult unforgivable not to use that power to some potent end.

That, being the list of what I believe rises to the level of complaint, I can on with my speech and my praise. The first and most apparent of which must be reserved for the characters. This may sound a bit backhanded as compliments go, though it is in no way intended as such, but the characters are in a sense two and a half dimensional. What I mean to say is that the prime characters all have defining and consistent traits that make them recognizable to young readers. Fflewddur has his penchant for stretching the truth, Gurgi his simplicity and hunger, Doli his cantankerousness, Eilonwy her precociousness and similes, and Taran his wish for heroism and tendency to judge things by their appearance. To an adult reader this may feel like a want of nuance, but I can think of few texts that I would trust more thoroughly to broach the subject of character with struggling or introductory readers. And this isn’t to suggest that these characters are chiseled in marble either as all are capable of great change and growth.

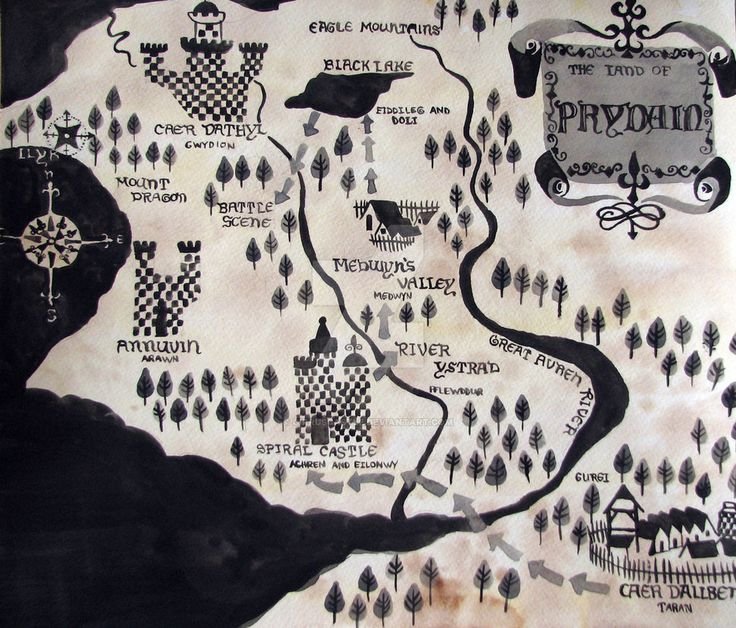

Prydain itself is also a great boon for the story and the series as a whole. Unlike Middle Earth, which has the feeling of endlessness in all directions with its massive scale, Prydain manages to feel intimate and close yet still large enough for grand adventures.

I’m sure much of this is due to the influence of Welsh mythology on Alexander’s storytelling. This first entry in a five volume series covers much of the area of the map and, as with the characters, gives young readers a geography they can grasp quickly, helping to visualize both direction and distance.

I’m accidentally making it sound as though this wonderful little novel is fit for nothing but teaching, but it is in fact much more than that. There is great charm and simplicity, whimsy and honesty here that, though harder to quantify, are no less treasures of inestimable worth. Without qualification, I dearly love this book and always have. So much so that I have, since my earliest memories of it, been forgiving of the Disney animated adaptation, which takes so many liberties that it might justly be called license, simply on the grounds that it visualized people and environs that I held in such high regard.

I will make one caveat for my affinity for the movie.

Was there ever a character done such wrong when being transferred from page to screen? Other than his truth telling harp and exclamations of “Great Belin!” there is nothing that survives the transcription. Clearly I’ve an affection bias, but I still hold out hope for a visualization of this character that retains the golden-haired youthful king and warrior of no mean worth that can be found in the pages of Alexander’s works.

I have returned to this book half a dozen times in my life, and certainly there are many more visits in my future. It is warm and comfortable, welcoming and inviting. Like Narnia, Middle-Earth, and Neverland, Prydain is etched eternal upon my heart and mind, and grateful I am that it is so. Without reservation or hesitation I would recommend it to any and all who have a love of ancient lands, mythic heroes, and are in need of revisiting the assistant pig keeper in all of us.

Leave a Reply